Andréa Givanovitch moves between cities, stages, and disciplines ... from Toulouse to Paris, Salzburg to Athens, dance to performance to visual art. At the center of it all: the body. As a dancer and choreographer, Givanovitch works with what’s most immediate and revealing – not only as a tool for expression, but as a way of thinking, of being in the world. As the protagonist of the FOD x INA KENT campaign, Givanovitch brings that perspective into focus. In this conversation, he speaks about learning through movement, finding authenticity in form, and the quiet rituals that shape how we move through public and private space. From questions of masculinity to the politics of touch, we talked about connection, choreography, and how what we wear, and carry, can shift how we feel.

A Q&A with Andréa Givanovitch | FOD x INA KENT

You work across dance, performance, and visual art … but if you had to introduce yourself in your own words, where would you start?

My name is Andréa Givanovitch. I’m a dancer, performer, choreographer, and artist currently based in Paris, originally from Toulouse, which is also where I recently co-founded my company, Melted Milk. I’ve been working since the age of 18 and began my training abroad, studying in Spain and Austria, before going on to work in Austria, the Czech Republic, and Greece. I’m currently working in the Netherlands.

One of the things that defines me most as an artist is the experience of travelling … connecting with different cultures, people, and artistic practices. That constant movement continues to shape the way I approach my work. At the moment, I’m working as a performer and choreographer in collaboration with companies based in Greece, France, and the Netherlands … and I’m also developing my own projects – I recently completed my second solo, and I am currently working on a new piece, which will premiere at the end of 2026 or early 2027.

As a dancer who’s constantly moving between projects, your path has taken you from Toulouse to Catalonia, Salzburg, and now Paris … a kind of choreographic map shaped by transitions and in-betweens. Looking back, which detours turned out to be essential?

I think I’ve been lucky – each experience, in its own way, turned out to be valuable. When I moved to Barcelona at 18, I joined a junior ballet company, which wasn’t really my thing artistically. It wasn’t the most fruitful time in terms of training or dancing, but it was hugely important on a personal level. It was my first time living abroad alone, learning a new language, and navigating a new culture. That experience pushed me to apply to national and contemporary dance schools, which eventually brought me to Salzburg.

Salzburg was definitely one of the most transformative periods of my life. I was there from age 19 to 25 … so quite a long time. I studied for four years at SEAD (Salzburg Experimental Academy of Dance), which is an incredible international space. It’s like a bubble of creativity inside a very conservative city. You’re surrounded by people from 50 different countries, and so many amazing artists come through. That’s really where I started to discover who I was … as an artist, but also as a person. After SEAD, I started working professionally with the Body Project Dance Company, which is also based in Salzburg. That was my first experience as a professional dancer, right out of school. So, if I had to name one place that truly shaped me, it would be Salzburg.

In “Leather Better,” you explore masculinity through repetition, exhaustion, and that “iconic leather jacket”. What kind of embodied knowledge does it take to question these structures from the inside out?

I think it takes a lot of introspection – and a real desire to question systems we often take for granted, like masculinity, brotherhood, or male dominance in both art and life. For me, it comes from a personal place. Because of my queerness, masculinity has always been something I was measured against, and often found lacking. I was made to feel I wasn’t "masculine enough" and that tension became a starting point in my choreographic practice.

My work often begins with something personal … my own relationships, experiences, or questions … and then becomes a way to connect with others. Leather Better deals with masculinity, but it’s also about how societal norms shape our bodies and our behaviours. And that’s something a lot of people can relate to, even if their entry point is different.

I’m especially interested in how physicality can carry these ideas. All of my pieces are very physical … because everyone has a body. And when you watch someone go through something physically, in an authentic way, it makes you feel something. It might be discomfort, recognition, resistance … but it creates connection. That’s what I’m trying to do with my work: to turn something deeply personal into something others can feel, question, and reflect on too.

Consent in dance isn’t always verbal. What have you learned about power, communication, and silence in bodies that work together … especially in improvisation or contact-heavy contexts?

I’ve come to understand that while consent in dance isn’t always verbal, sometimes it really needs to be. In our field, there’s a lot that goes unspoken, especially because we’re constantly working with our bodies. Dancers tend to have a heightened awareness of their own bodies and of others’, but that doesn’t mean everything can or should be left to intuition or physical cues.

I’ve learned that verbal communication needs to come first. It sets the ground for any nonverbal exchange to happen in a space that actually feels safe. When there’s room to talk and set boundaries clearly, then the silence, the improvisation, the contact can become something meaningful, rather than invasive or confusing.

I’ve been in performances where dancers enter the audience and start touching people without asking, and honestly, it doesn’t always feel appropriate. People should always have the choice to engage … or not … in physical contact. A friend of mine, a choreographer in Finland who works with participatory performance, told me they give out stickers at the start of a show: red or green, to signal whether audience members are open to touch or not. It’s a simple idea, like a children's game … and if kids can understand it, adults definitely can too.

I think we need more of these clear, thoughtful frameworks to create environments where people feel agency over their bodies. Because physical connection can be incredibly liberating … but without consent, it can also be deeply upsetting or even traumatic.

In dance, movements and gestures constantly circulate – across bodies, stages, platforms. Do you think originality is still possible? Or is everything, in some way, already a reference? How do you personally navigate questions of authorship and ownership in your work?

I think the dance field today has shifted in a way that puts pressure on artists to constantly create. In the past, there were fewer choreographers, and more opportunities for dancers to work within existing companies or productions. Now, with many of those structures shrinking or disappearing, a lot of dancers are creating their own work – not only out of artistic desire, but also because they can’t find employment as performers. So, we see more and more work being made, which is exciting, but it also raises new questions around authorship and originality.

I mean, how do you claim ownership over a movement? On one hand, there are choreographers who have developed movement languages so specific that anything resembling their work can be perceived as plagiarism. But from a legal point of view, there’s very little framework around that – at least not in dance. It’s hard to “own” a movement or a quality. I think, again, it comes back to authenticity. You know when something emerges from your own lived experience, your body, your questions … versus when you’re reproducing something you’ve seen elsewhere.

At the same time, I do believe that nothing is entirely original. I keep thinking of Julian Rosefeldt’s idea in Manifesto: “Nothing is original.” Everything I make carries echoes of performances I’ve seen, books I’ve read, films I’ve watched, choreographers I’ve worked with. My work is shaped by all of that. And that’s okay. What makes it original is the specific constellation of those references through me. I’m the only person who’s had exactly my set of experiences, with those people, in that order, in those contexts. That combination is unique – and that’s where my authorship lies.

For example, in my first solo Some Faggy Gestures, the entire piece was built around the works of other queer artists. Like an homage, a collection, a rewriting through my own body and perspective. It was deeply personal, but at the same time full of citation. For me, acknowledging those references is also a way of making them visible – of honoring their influence and giving them space within my own work.

So, no – I don’t believe in making something completely new that no one else has ever done before. That’s not the point. The point is to create something that is honest, situated, and in conversation – with others and with yourself.

This might be a weird question … but let us explain the context: As brands operating in Vienna … and as people living here … we often sense a tension in the city: Vienna likes to present itself as open and progressive, but in everyday life, that openness can feel conditional. Certain forms of visibility still provoke discomfort and “bodies” still trigger projection, judgment, even harassment. How do you experience Vienna in this sense … especially when it comes to moving through public space with your body, like visibly … like in our campaign?

There’s a lot I could say about Vienna. I’ve experienced the city from different perspectives: first from Salzburg, then after moving away and coming back. When I lived in Salzburg, Vienna felt like this open, progressive place, a city where I could finally be myself, do things freely, and not feel so observed or judged.

But then I left, spent time elsewhere, and returned. And I realized … actually, Vienna isn’t that open. Or not in the way I once thought.

There’s something about the way people interact with you on the street, the way they stare or even shout at you for no reason. When I was living in Austria long-term, I got used to that kind of thing. But now, coming back, I notice it again. There’s a tension. It made me realize how easily one starts to adapt, to shrink or quiet themselves to avoid drawing attention. And how much inner resistance or resilience it takes not to fall into that pattern.

Of course, it’s not always easy. I’ve been lucky here in Vienna because I’ve grown within artistic bubbles that feel open and supportive. But it really depends on where you are and who you’re with.

Take Club U, for example. It’s right in a subway station. Rhinoplasty is a queer space with this intense, beautiful energy. But the moment you step outside, you’re surrounded by people who might look at you weirdly or even say something hostile. That contrast really captures Vienna’s duality: bubbles of freedom inside a city that’s still full of friction.

That’s why these group dynamics – this sense of collective protection – are so essential. When we were shooting the campaign, I didn’t feel any fear or discomfort, because I was surrounded by all of you. The team created a safe environment where I could just be – walk around, wear what I wanted, not have to think twice about how I looked or moved. So, for me, that’s one of the only ways to deal with it: surrounding yourself with people who create that kind of safety.

What’s also interesting about Vienna is that there’s so much visible messaging around queerness – rainbow flags everywhere, official slogans, public campaigns. It might even be the city where I’ve seen the most institutional communication around LGBTQ+ visibility. It’s funny. Vienna is trying – but at times, it feels like it edges into queerbaiting … so the reality on the street doesn’t always match the narrative.

You recently walked for Rick Owens – a show that drew quite a bit of attention. What was that experience like for you? And how did it differ from how you usually inhabit your body as a dancer or performer?

It was fun to do … definitely a first for me. I’ve worked in fashion before, but I’d never walked in a show. The show itself was one thing, but everything that surrounded it – the hair, the makeup – that was a whole other experience. I spent hours in hair and makeup. There’s just so much visual stimulation, and so many expectations around how you look. It sounds obvious, but it really hit me in a different way when I was in it.

There was a kind of magic in being part of that world for a day. But I’m not going to lie – I don’t think it’s something I’d want to do full-time. That said, there’s something … well kind of magical about Rick Owens. After the show, we went to his retrospective at the Palais Galliera, and being there with him, seeing the full scope of his work and the way he thinks – how he designs clothes in a way that shapes bodies – that was really exciting and inspiring.

At the same time, fashion is such a particular world. It can be quite superficial. People interact with you in ways that feel very specific to that space – and the people coming to the show really take themselves seriously. Coming from a different background, maybe it’s just my small window into it, but sometimes I felt like … can we all just chill a bit? It’s amazing, yes, but it could all be held with a bit more lightness.

Do you think clothing can add confidence? And what kind of thoughts or experiences come up for you when you think about the relationship between what you wear and how you inhabit your body … in daily life or in your practice?

The way you dress really affects how you relate to your body. I never quite understand when people say they don’t care what they wear – maybe I overthink it, but for me, it makes a big difference. The way I dance in shorts versus in training clothes is completely different. It’s about the feeling, but also the visual – how I see myself, how others see me.

I find it fascinating that clothing can shift how I experience my own body. That’s why I pay a lot of attention to what I wear – whether I’m creating my own work, dancing for someone else, or just rehearsing. Feeling comfortable and empowered in what I’m wearing is important. Not only because we work with our bodies, but because performance is also a visual art form and costumes and clothing are part of the language. And I feel like that aspect sometimes gets overlooked, but for me, there’s a strong and very conscious connection between what I wear and how I move.

We feel like, there’s something ritualistic about putting on lingerie – especially something as thoughtful as Full Of Desire. Do you have a personal ritual around dressing (or undressing)?

I wouldn’t say I have a ritual around dressing or undressing – at least not yet. I think that also has a lot to do with how underwear has been treated in culture. There’s always been so much emphasis on lingerie for women – aesthetic, emotional, symbolic – whereas underwear for men has mostly been approached in a very practical way. For a long time, I wore boxers, until I realized how much better I felt in briefs. It made me more aware of how underwear can actually change how I feel in my body. Still, it wasn’t something I thought about much on a daily basis. But seeing a brand like FOD made me realize that there is another aspect to lingerie that hadn't really crossed my mind before. So, while I don’t have a ritual yet, it’s something I’ve been exploring more and more – choosing different underwear depending on how I feel that day. Sometimes practical, sometimes something else entirely. I’ve been thinking about getting a jockstrap for a long time, but I haven’t quite made that move yet. There’s something about still figuring it out – slowly learning how to fulfill myself in that space.

Lingerie is so often designed for someone else’s gaze. What shifts when it’s about your own gaze?

Lingerie is so often thought of in relation to someone else – usually in a sexual or heteronormative context. But I think I’m now in the process of figuring out what it means to wear it for myself. Like putting on a thong and feeling hot, but not because I want someone else to look at me that way. Just because I feel good in it … which is a pretty good feeling. So … I guess I’m still in the process of being able to fully answer that question.

Imagine someone finds your bag and looks inside … what do you think they’d assume about you?

It’s funny, because I always have these things in my bag – lip balm, perfume, hand cream, gel – all the little beauty or toiletry items people usually keep at home. But I never actually use them at home. You know, the typical routines like putting on face cream? I just don’t do that when I’m at home, I’m always all over the place. So instead, I keep everything with me, packed in a little case or bag inside my bag. Plus, I also nearly always have a book with me. And rings – I always have rings. So, if someone found my bag, they’d probably think I’m super organized and well-prepared. Which isn’t really true. The truth is, I carry all this stuff because I know I won’t be prepared – so I take it all with me, just in case.

A bag is such a personal object … always close to the body, often revealing more about us than we realise. Do you feel yours says something about who you are, or how you move through the world?

My bag says that I’m constantly on the move. I think it reflects the way I move through the world: always shifting between places, always carrying a little more than I probably need.

INA KENT bags are made to adapt – they shift, transform, unfold. Did you explore different ways of wearing yours?

I love wearing it as a shoulder bag so much that I haven’t really explored the other ways yet. It just works for me. And honestly, you wouldn’t believe how many people have commented on it. What I love about the design is how it’s both simple and intricate – there’s something very clever about it. Especially in summer, when I tend to wear plain, minimal outfits, the bag really makes everything pop.

What are your favourite pieces in your closet?

My black Levi’s jeans … they’re a staple. I can wear them anytime, anywhere. But if I want to go for something a bit more fun, there’s this black corset my friend Fiona from Vienna gave me years ago. It’s my go-to when I want to feel like a hot, cool, chick and sexy. And then … I have these incredible knee-high black snake-print boots that I found at a flea market. I saw them and thought, “There’s no way they’re my size.” But somehow – for some magical reason – they were exactly my size. They’re super high and honestly a bit painful to wear, so I don’t put them on often. But they’re amazing.

Which tracks are you currently playing on repeat?

Right now, I’ve got the Oklou album „choke enough“ on repeat.

What was the last piece – dance, theatre, performance, or otherwise – that really moved you? And do you remember why?

I’ve been to a ton of great shows recently … but I’ve been thinking about this one, especially because it connects to the topics we’ve talked about. The last piece that really moved me was The Brotherhood by Carolina Bianchi – she’s a Brazilian theatre director based in Amsterdam. It’s the second part of her Cadela Força trilogy, and it focuses on masculinity as a closed circle … one that protects men, enables violence, and still commands admiration, especially in the arts. The piece explores both confrontation and fascination with male dynamics. Bianchi really dives deep into the contradictions, particularly the uncomfortable space where we find ourselves drawn to artists whose work we admire, but whose actions or values we strongly reject. It’s not about simply separating the art from the artist, it’s about sitting with that friction, the emotional tension of admiring something that maybe shouldn’t be admired anymore.

You're currently living in Paris. How do you spend a day there when you have no obligations?

On a free day in Paris, I love going to museums – recently I went to the Centre Pompidou to see the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition, which was amazing. And … Lorde was there! The Pompidou is one of my favorites, but Paris is full of incredible museums – the Bourse de Commerce, the Musée de l'Orangerie, the Pinault Collection, the Grand Palais (...). For lunch, I’d go to IMA Cantine – it’s a great vegetarian spot by the canal. If it’s a sunny day, I’d head to the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in the 19th arrondissement – it’s one of the most beautiful parks in the city. In the evening, I’d probably get some Chinese food in Belleville, and if I’m in the mood to go out, I’d head to La Station – Gare des Mines. They usually have really great parties.

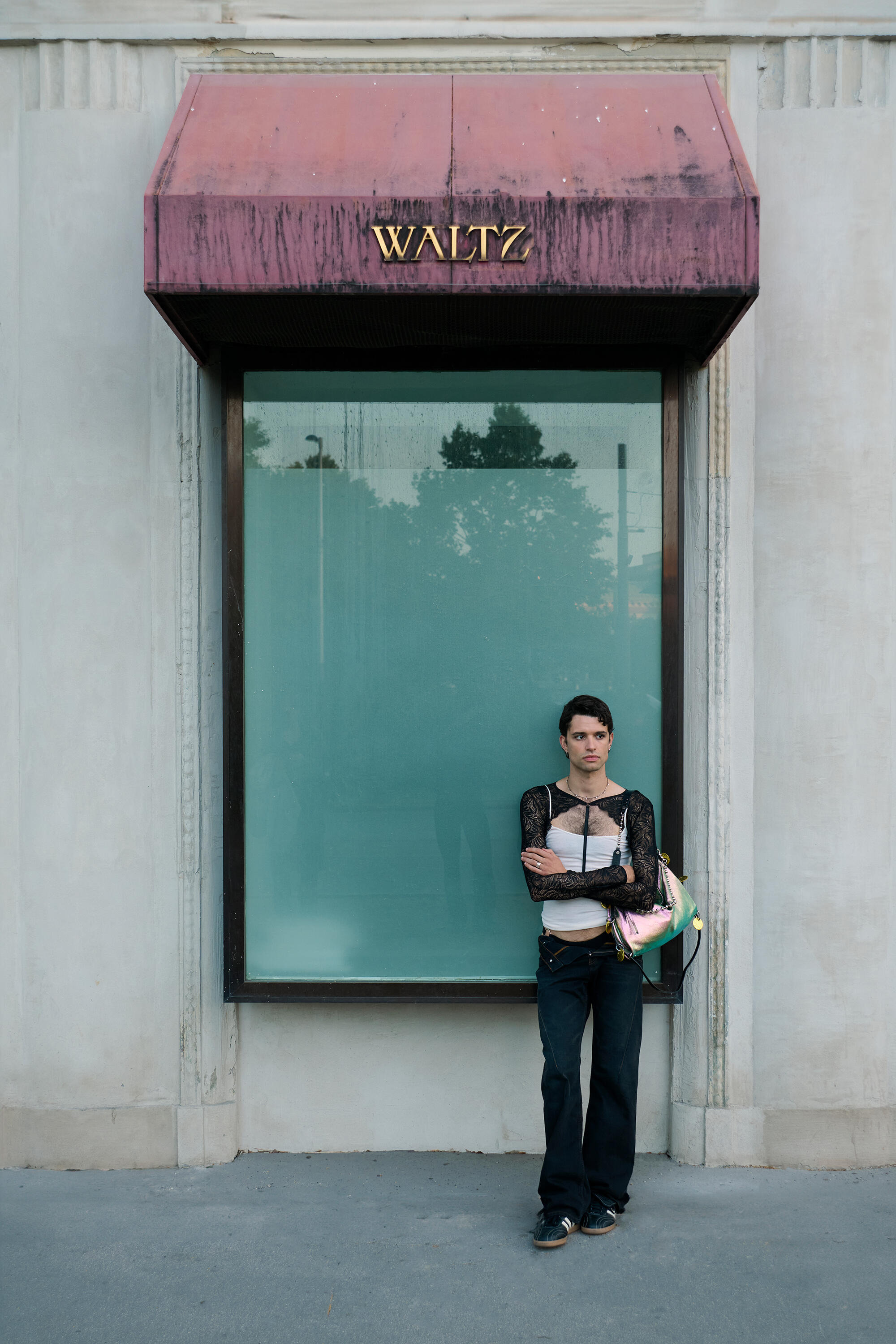

ANDRÉA WEARS DINKUM ed.2 two-tone leafy rose, FOD Pascal Swim Speedo & Lois Open Sleeves.

Photos by (c) Pascal Schrattenecker.

Discover FOD on Instagram.